The Amazon in Suriname

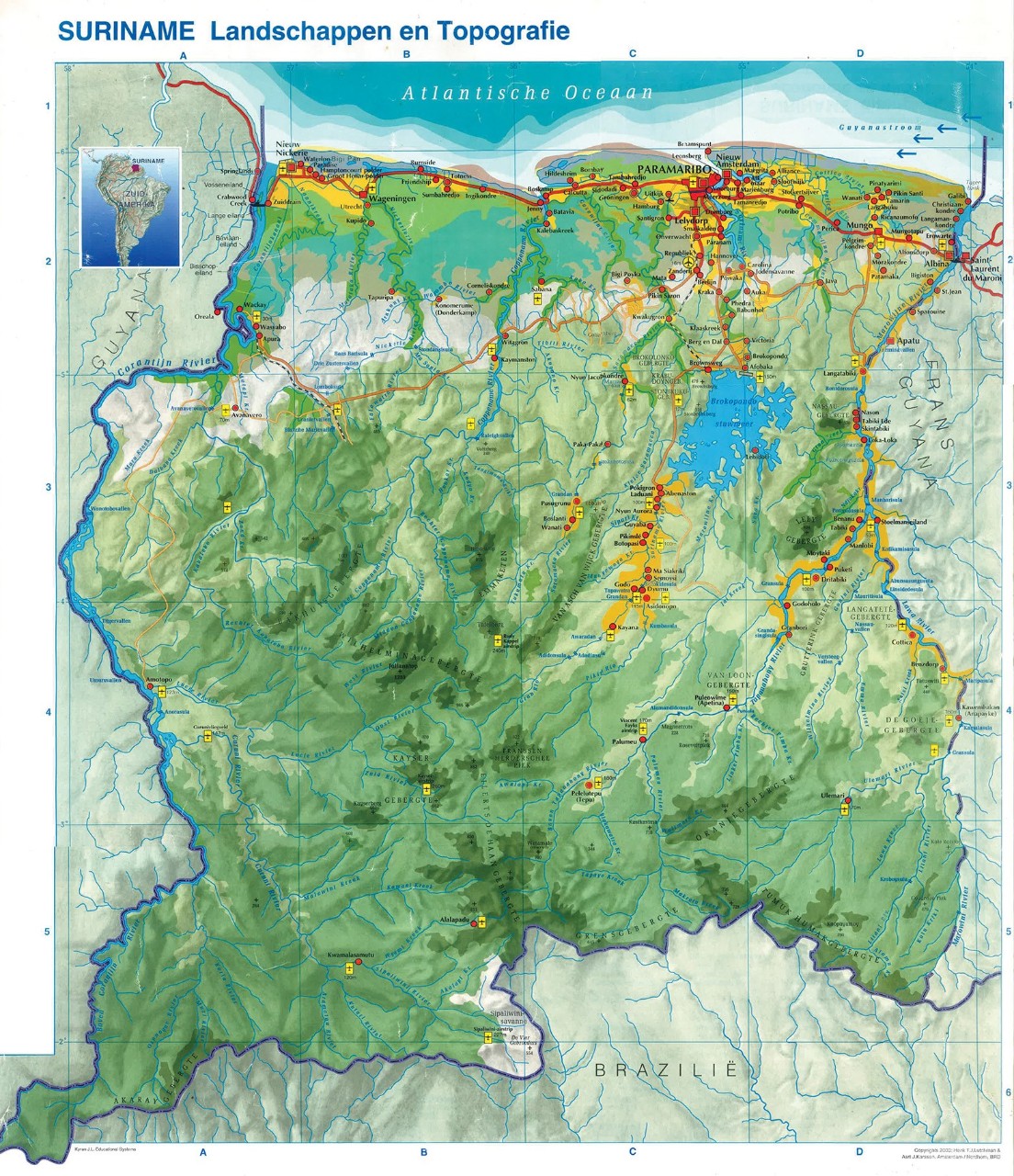

Geographical borders: to the East, French Guiana; to the West, Guyana; and to the South, Brazil. In the North, Suriname borders on the Antlantic Ocean.

Geographical borders: to the East, French Guiana; to the West, Guyana; and to the South, Brazil. In the North, Suriname borders on the Antlantic Ocean.

Information about Suriname and the Diocese of Paramaribo

Geography

Suriname lies on the North-Eastern coast of South America, between French Guiana in the East, Guyana in the West, and Brazil in the South, between 54° and 58° Western longitude and 2° and 4° Nothern latitude. The country covers a surface area of 163,821km2 (63,252 sq. miles), of which the largest part (approx. 80%) is covered by pristine rainforest. The South of Suriname is part of the Amazon Rainforest. It holds a considerable amount of natural wealth in terms of biodiversity, freshwater resources and cultural heritage. However, the isolation that has protected Suriname’s southern unique

ecosystem is now threatened by high commodity prices which have encouraged the spread of small-scale activities, such as gold-mining, logging, hunting, poaching and other potentially unsustainable activities. When undertaken without due care, these activities can degrade water quality within the region’s extensive system of waterways and reservoirs which could harm the South of Suriname’s unique ecosystems and could cause great impact on Indigenous communities living in the south who rely heavily on the natural resources for hunting, fishing and other traditional purposes such as medicinal plants. Also, as is the case in many countries around the world, long-term sustainable economic development in Suriname is threatened by climate change. Availability of food, freshwater resources and habitat vulnerability are among the most prominent issues related to climate change and likely to have disproportionally greater impact on Indigenous communities living in the south.[2]

Demographics

According to the statistics of the national census of 2012, Suriname has a total population of 541,638 which is divided among different ethnic groups[3]: Indigenous[4], Maroon[5], Creole[6], Afro-Surinamese[7], Hindustani[8], Javanese[9], Chinese[10], Caucasian and mixed. In the last two to three decades, there has been a large influx of new immigrants, mainly from China and Brazil, and the latter is often considered and referred to as a separate ethnic group. According to the division made by the statistics bureau, the Hindustani’s are the largest ethnic group in the country with 148,443. They are followed by the Maroons with 117,567, then the Creoles/Afro-Surinamers with 88,856, the Javanese with 73,975 the group of mixed ethnicity with 72,340, and finally the Indigenous with 20,344. All the remaining ethnic groups have less than 10,000.

Politically, the country is divided into ten districts, of which six are in the coastal plains. From East to West these districts are: Marowijne, Commewijne, Wanica, Saramacca, Coronie and Nickerie. The other four are Para, Brokopondo and Sipaliwini, the latter being the southernmost and largest, covering approx. 75% of the country, but with the lowest population density. The tenth district is the capital city, Paramaribo, which has the largest population: 308,888 (57% of the total population).

The largest numbers of Indigenous and Maroons are found in the remote interior of Suriname, where they live in villages mainly along the major rivers of the country. Both ethnic groups consist of different tribes which are individually concentrated in particular areas of the country. The Hindustani and Javanese are also historically concentrated in certain areas i.e. districts of the country, namely Saramacca and Nickerie.

Languages

Apart from being multi-ethnic, the country is also multi-lingual. Since the colonial rule by the Kingdom of the Netherlands, the official language of Suriname is still Dutch, be it with some slight differences from the Dutch that is spoken in the Netherlands. It is noteworthy, however, that even though Dutch is the official language, far from all people in the country can speak, read or write in that language. The most widely spoken language is Sranantongo, often referred to as the lingua franca of the country. By all standards, Sranantongo is a language in its own right, but in spite of it being the most widely spoken language, very few people know how to read or write it (properly), even though it has an official spelling and grammar.

The different ethnic groups all have their own native languages too. The Hindustani speak Sarnami, which is a local variation of the Hindi that their ancestors spoke. So too with the Javanese, Bangsah Jawa, which is still very close to the language spoken in Java. The Indigenous tribes have all retained their original languages, but the continuation of it is endangered as the younger generations are speaking it increasingly less.[11] The different Maroon tribes also have their own languages. With the recent influx of immigrants from China and Brazil, their languages have now also become part of the linguistic landscape of the country.

Religious data

Another aspect of Surinamese society is the multi-religious composition of the population. A first division gives the following data: Christians 40.7%, Hinduism 19.9%, Islam 13.5%, others[12] 10.2%. A more specific delineation of the religions (according to denomination) is:

- Christians: Roman Catholic 117,261 (21.6%), Lutherans 2,811 (0.5%), Evangelicals 60,530 (11,18%), Moravians 60,420 (11,16%), Reformed 4,018 (0.7%) and other Christians 17,280 (3.2%);

- Hinduism: Sanatan Dharm 97,311 (18%), Arya Dewaker 16,661 (3.1%) and other forms of Hinduism 6,651 (1.2%);

- Islam: Sunni 21,159 (3.9%), Ahmadiyya 14,161 (2.6%) and other Islamic denominations 39,733 (7.3%);

- Other religions: Jehova’s Witnesses 6,622 (1.2%), Agama Jawa[13] 4,460 (0.8%), Judaism 181 (0.03%), Winti[14] 9,949 (1.8%) and others 4,630 (0.9%)

In total there are 40,718 people who claim to have no religious affiliation.

Diocese of Paramaribo

The Catholic Church in Suriname was elevated to the status of Diocese on August 24, 1958. The first Bishop of Paramaribo was Most Rev. Stephanus Kuijpers, who was the Apostolic Vicar of the Vicariate of Suriname. He was succeeded by Most Rev. Aloysius Zichem, the first local Bishop, in 1971. Bishop Zichem stayed actively in office until the end of 2002, when he was incapacitated by a brain haemorrage. The Pope granted his resignation in 2004, and was succeeded by Most Rev. Wilhelmus de Bekker in January 2005. Bishop De Bekker resigned in 2014 after having reached the age of 75[15]. He was succeeded by Most Rev. Karel Choennie, who took office in January 2016 and is the current Bishop of Paramaribo.

After a long history with many missionaries (priest, religious brothers and sisters) from the Netherlands and Belgium, the Diocese has entered an era where almost all of those missionaries have passed away or returned to their native country. Only three of those missionaries are still present in the Diocese at the moment, all of them retired but assisting the Diocese wherever they can, but not assigned to a parish or other pastoral ministry.

Together with the abovementioned priests and including Bishop Emeritus Wilhelmus de Bekker, Bishop Choennie has 17 ordained ministers in the Diocese. Seven of these priests are age 60 or older. There are seven diocesan priests[16], four from the congregation Oblates of Mary (OMI), two from the congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer (CSSR), three from the Society of the Divine Saviour (SDS), and one Vincentian (CM).

At the moment there are three communities of consecrated life in the Diocese: the Daughters of Mary Immaculate (FMI, two sisters), the congregation of Fransiskus Charitas (FCh, three sisters) and the Servants of the Lord and the Virgin of Matará (SSVM, four sisters). There are no male communities. There are also seven permanent deacons, of whom six are local and one is from Brazil, working in Suriname.

Bishop Choennie has to carry out his pastoral responsibilities for almost 120,000 Catholics, spread across the whole country in more than 60 parishes and base communities, with the help of only seventeen priests, nine religious sisters and seven permanent deacons. The positive side of this challenge is that the laity have gotten increasingly involved in pastoral ministry and in some cases take up leadership positions, especially in parishes of church communities, where there is no resident priest or the visiting priest is present only a few times during the year.

One major form of lay leadership is the institute of catechists, who work mainly in the remote villages in the interior of Suriname. Their task is to bring together the faithful in their village for prayer and other forms of worship, as long as a priest is absent. They are also in charge of catechesis, esp. in preparing parents for the baptism of their children. They also preside at funerals and as such they maintain the pastoral presence of the church in their villages. At present, there are more than 100 catechists active throughout the Indigenous and Maroon villages in the interior.

The congregations of religious sisters and brothers[17], who were at some point in the history of the local church present in large numbers, established many works of charity in the country, most of which still exist today. There are over 70 Roman Catholic schools throughout the country and it is safe to say that all these schools were established by the religious sisters and brothers. These schools are now supervised and managed by the Roman Catholic Board of Education (RKBO). Another icon of the presence of religious sisters in Suriname is the Roman Catholic hospital, Sint Vincentius Ziekenhuis, established by the Sisters of Charity of Tilburg more than 100 years ago. These sisters were also responsible for the establishment of a nursing home for senior citizens, Gerardus Majella. This example was followed by the FMI sisters and they established Fatima Oord, also a nursing home for senior citizens.

Apart from their care for young people through schools, the religious also established various boarding homes, with which they catered for the children and young people from remote places who needed residence in Paramaribo or elsewhere to attend school. Only three of these boarding homes still exist today. The Brother of Mercy of Tilburg focussed a lot on vocational education and also set up small business to encourage entrepreneurship among the pupils of their schools. Some of these business ceased to exist and others were taken over by private individuals.

Apart from the difficulties in ministering to the local church with such a small number of clergy and religious, the sustainable continuation and maintenance of all these aforementioned works of charity is also a major challenge for the Bishop. Even though much of responsibility rests in the hands of the laity, the Bishop cannot overlook the necessity of the actual presence of the church in these institutions, in the form of ordained men and professed religious who minister to the spiritual needs of those whom these institutions are focussed on.

There are also large parts of the nation – both geographically as well as ethnically – where the church still needs to make its presence felt. In the distant past, the leadership of the church in Suriname had adopted the strategy of specialized ministry, whereby the different ethnic groups (each with its own language) where ministered to in their own language. Thus the pastoral ministry was categorized in ministry for the Hindustani, the Javanese, the Chinese, the Maroons and the Indigenous. However, the wave of nationalism, that occurred in the 1960s, resulted in the abandoning of this strategy and in its place the decision was made to approach the faithful as one Surinamese nation and the ministry in the languages and cultures the different ethnic groups was replaced with a ministry in Dutch or Sranantongo alone. Apart from the Afro-Surinamese groups, the other groups felt they could no longer identify with the church and their numbers diminished. However noble the intentions of fostering patriotism and a unified nation, this decision nonetheless left the church with a great void in the ministry to the total population.

In recent years, the categorized ministry is gradually returning, especially in the case of the large number of Brazilian immigrants in the country. More than two decades ago, the Redemptorist provice of the Netherlands handed over their mission in Suriname to the Brazilian province. Ever since Brazilian Redemptorist priests have been present in the local society, the Brazilian Catholic community in Suriname has grown and becomes increasingly active in the church. The same is seen happening now with the Javanese Catholic community, since the arrival of a Vincentian priest from Indonesia and the establishment of a community of religious sisters of Fransiskus Charitas, also from Indonesia.

The fear of causing division in the total Catholic community with a categorized ministry (which led to its abandonment in the 1960s) had now been proven unfounded. The Bishop is therefore looking for clergy and religious, who are fluent in one or more of the local languages, to diversify and strengthen the mission of evangelization of the Church in the society of Suriname.

(more information bisdomparamaribo.org )

[2] This information is obtained from the organization Conservation International Suriname, with which the Diocese of Paramaribo has signed a agreement of collaboration on the matter of preserving the ecology and biodiversity of the country.

[3] The titles for the different ethnic groups are taken from the report of census of 2012. The statistician used the titles that the respondents themselves used to describe their ethnicity.

[4] These are the autochtones inhabitants of the country and comprise different tribes, living mostly in the rainforest in remote villages in the interior.

[5] These are the descendants of the people from Western Africa, who were brought to Suriname in the 18th and 19th century to work as slaves on the plantations owned by the Dutch colonizers.

[6] This term is used mostly for people from African descent living in cities in the coastal area.

[7] This term is preferred by some people of African descent over the term ‘creole.’

[8] This term refers to the descendants of the immigrants from India, who came to Suriname as indentured labourers toward the end of the 19th century, when slavery was former abolished.

[9] This term refers to the descendants of the immigrants from Indonesia, particularly from the island of Java, who came to Suriname under the same conditions as the immigrants from India.

[10] The Chinese were the first Asian immigrants to the country. They came before slavery was abolished and before other Asian groups. Presently, a distinction is made between the descendants of these immigrants, who came to Suriname at the end of the 19th century and also the beginning of the 20th century, and the new immigrants from China, who arrived here in the last two to three decades.

[11] This same is true for most native languages of the different ethnic groups. Because of the education they receive and for reasons of social mobility, the younger generations of the different ethnic groups are not motivated to retain the native language of their ancestors.

[12] This number includes the adherents of Winti, which is a local religion derived from the ancestral beliefs of the descendants from Western Africa, as well as the native religion of the Indigenous.

[13] The native religion of the descendants from Java, Indonesia, sometimes referred to as a form of Hinduism.

[14] See footnote #11.

[15] Bishop De Bekker is currently the parish priest of the St. Thaddeus parish in Saramacca.

[16] Of the seven diocesan priests, four are local, one from the Netherlands and two from Nigeria.

[17] The following orders had large communities in Suriname but are no longer present: the Franciscan Sisters of Roosendaal, the Franciscan Sisters of Oudenbosch, the Sisters of Charity of Tilburg, and the Brothers of Mercy of Tilburg. Still present is the congregation of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate, a local order of diocesan right which originated through the Franciscan Sisters of Roosendaal.

******************************************************

Documentary into the lives of adolescents in Suriname’s Amazon

"I Choose Me” is a documentary into the lives of adolescents in Suriname’s Amazon. The epic story of 4 indigenous adolescents that give testimony as to what their life is like and the choices they have made for survival, protection and reaching their full potential. The documentary also displays their living conditions and related issues ranging from environmental hazards to the lack of education opportunities. From shots taken themselves in Suriname’s beautifully conserved Amazon, to shots within the goldmines of Suriname’s interior, ‘I Choose Me’ brings you through the emotional journey of these adolescents, their fears, hopes, dreams, thoughts and choices, to better their own lives within their possibilities.